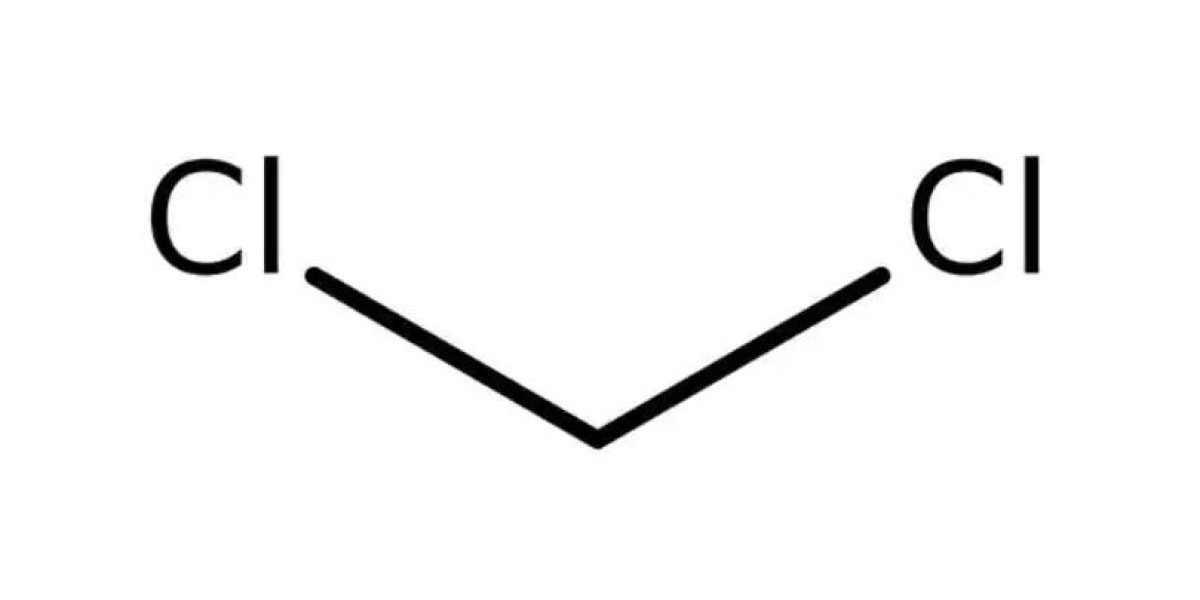

It has attracted a lot of regulatory scrutiny because it's not exactly lemonade, and we process more than £200 million of lemonade a year. The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration has many controls on the use and acceptable levels of dichloromethane, among other things: Dichloromethane has been a reportable Toxic Release List chemical since 1987, it is a hazardous air pollutant under the Clean Air Act, a drinking water pollutant under the Safe Drinking Water Act, and more. It has been disappearing from paint thinner formulations for years (falling into this category since 2019), and if it is still used in such consumer products, it must be labeled under the Consumer Product Safety Commission's Federal Hazardous Substances Act.

Most importantly, however, the 2016 amendment under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) requires the EPA to re-examine the safety of existing industrial chemicals through a risk assessment process (rather than simply relying on observational epidemiology, etc.) "without regard to cost and other non-risk factors," the EPA said. To determine whether a chemical poses an unreasonable risk of harm to health or the environment, including an unreasonable risk to potential exposures or susceptible subgroups identified as relevant to the risk assessment..." Dichloromethane (dichloromethane sds) is second on the list, after asbestos. In November, the agency determined that it had indeed issued the aforementioned unreasonable risks to human health, so some kind of action was imminent, even with the surprising severity of the latest proposal. This is the final risk assessment. It's very detailed.

The EPA proposal does make room for "critical manufacturing" processes, such as the production of non-ozone-depleting alternatives to freon, military and aerospace uses, etc., but those processes would be subject to strict workplace exposure controls. The agency noted that some industrial facilities here have already met the standards, so these adjustments have been in the works for some time. But it will be interesting to see how actual military and aviation users react; Their views may be very different. Chemical manufacturing is another industry I'm looking forward to hearing about - for the most part, the fine chemicals industry is increasingly avoiding solvents due to these environmental controls and higher waste disposal costs, but it's not going away and the remaining uses may be hard to replace. You can apply this statement across the board - reduced usage over the years means that what's left will be correspondingly harder to change.

But the various uses I've been working on for decades, I can't imagine meeting those standards: pouring solvents out of jars into a graduated cylinder, flowing down the column, then collecting distillates in conical flasks and test tubes - that sort of thing. If we follow the written instructions, we will have to consider our bench chemical solvent options. Could it? Once the proposed rule is published in the Federal Register, the agency provides a 60-day comment window for the public to pursue extensive lobbying (and even litigation) on behalf of industry users who feel they have no choice.

So, to be honest, the last thing I want is for this to be achieved smoothly within the proposed 15 months. Updates are coming, I believe.